Introducing Hyperview: a server-driven mobile app framework

In a recent blog post, I explained why the Instawork engineering team moved our web development from the popular SPA + API architecture to server-side rendered web pages. Server-side rendering lets us develop new features quickly using a single language (Python) and a single integrated framework (Django). Adding Intercooler.js to the mix gives us SPA-like interactivity, while still keeping all business logic and HTML rendering on the server.

The level of productivity we were able to achieve with Django + Intercooler was incredible, but the impact was relatively small. That's because Instawork's main platform is not the web, but mobile. The vast majority of our users access Instawork through native iOS and Android apps. And on mobile, we were still using the very architecture we just ditched on the web: a thick client (written in React Native) pulling data through a JSON API.

Thick clients are the industry-standard architecture for native mobile apps, but we started questioning why it seemed to be the only option. Thick clients make sense for some categories of apps like games, photo tools, or anything that relies on local state & data. But a thick client is not a great fit for networked apps like marketplaces or social networks, where an Internect connection is a requirement for the app to function. The root of the problem:

Implementing a networked app as a thick client requires business logic to be split and duplicated between the backend and frontend.

- A thick client needs to know the possible API endpoints and JSON format of those endpoints, resulting in duplicated code.

- A thick client contains logic determining how to validate user input and what kind of inputs to ask for. The server also needs to perform this validation, resulting in more duplicated code.

- A thick client contains conditional logic to determine how to render API data and how to navigate between screens based on user interactions or backend responses. This critical logic exists exclusively on the frontend.

The code duplications add complexity and development time, since the same logic needs to be implemented twice. The frontend/backend splits add headaches once the userbase is on multiple app versions, with each version making slightly different assumptions but all interacting with the same backend.

Once we realized that networked apps are a poor fit for thick clients, we started looking for a thin-client mobile framework to adopt. The best solution out there seemed to be HTML + JS web apps bundled in a native wrapper (such as Cordova). We found this solution to be a little clunky for our needs: HTML was not designed with mobile UIs in mind, resulting in poor performance and less than ideal UX.

We didn't find an existing thin-client framework for native mobile apps. So we built our own.

![]()

Instawork is excited to announce Hyperview, our open-source framework for developing mobile apps using the same thin-client architecture that powers the web. Hyperview consists of two parts:

Hyperview XML (HXML): a new XML-based format for describing mobile app screens and user interactions. HXML's building blocks reflect the UI patterns of today's mobile interfaces. Features like stack & modal navigation or infinite-scrolling lists can be defined with a few simple XML attributes and tags.

Hyperview Client: a mobile library (on top of React Native) that can render HXML. The client can render any HXML screen and handle navigations & interactions by making further HXML requests.

On the web, pages are rendered in a browser by fetching HTML.

With Hyperview, screens are rendered in your mobile app by fetching Hyperview XML (HXML).

HXML

In HXML, mobile app screens are defined in XML format using a core set of attributes and tags. The experience writing HXML should feel familiar to anyone who's worked with HTML:

<doc xmlns="https://hyperview.org/hyperview">

<screen>

<body>

<text>Hello, Hyperview!</text>

</body>

</screen>

</doc>

But there are some significant differences between the two formats. HTML was designed to represent static text documents. HXML, on the other hand, is designed to represent dynamic mobile apps.

Native syntax for common mobile UI elements

HXML has tags for common mobile UI patterns, like section lists or headers. This makes it easy to create a list with sticky sectioned headers, without the need for scripting or tricky CSS:

<section-list>

<section>

<section-title><text>Section 1</text></section-title>

<item key="1"><text>Item 1</text></item>

<item key="2"><text>Item 2</text></item>

</section>

<section>

<section-title><text>Section 2</text></section-title>

<item key="3"><text>Item 3</text></item>

<item key="4"><text>Item 4</text></item>

</section>

</section-list>

Custom input styling

HXML's input elements allow complete control over styling to create more customized forms. In HTML, input elements are limited to certain appearances and semantics, like "radio" or "checkbox". In HXML, flexible elements like <select-multiple> and <option> can be rendered as checkboxes, tags, images, or any other appropriate visual treatment.

Rich interactions without scripting

In HTML, the basic user interaction is the hyperlink: users click an element, and the browser requests a new page.

<a href="/next-page">Behold, the power of the hyperlink!</a>

Hyperlinks on their own are not expressive enough to build interactive web apps, so developers use Javascript to create more complex interactions.

In HXML, the behavior syntax can express a large class of user interactions with declarative markup.

- The

triggerattribute allows behaviors to execute not just on press, but under many other types of user interactions, such as a pull-to-refresh. - The

actionattribute allows a behavior to navigate to a new screen. But it also supports modifying the current screen by replacing, appending, or prepending HXML content to elements.actiongives developers the power of AJAX without needing to write callbacks or promises in code. - Declarative loading states can hide or show parts of the screen while requests are in-flight.

Take this example HXML snippet:

<body id="Body">

<list>

<behavior trigger="refresh" href="/news" action="replace" target="Body" />

<item key="1" href="/news/1">

<behavior trigger="press" action="push" href="/news/1" />

<behavior trigger="longPress" action="new" href="/news/1/settings" />

<text>Story 1</text>

</item>

</list>

</body>

The example contains three <behavior> elements, which declare (respectively):

- When the user does a pull-to-refresh gesture on the list, make an HTTP request to fetch

/news, and replace the element with idBodywith the HXML response content. - When the user presses the item, make an HTTP request to fetch

/news/1, and show the content in a new screen pushed onto the stack. - When the user long-presses the item, make an HTTP request to fetch

/news/1/settings, and show the content in a new modal above the current stack.

With HXML, it's possible to create a rich mobile UI in pure XML, without the need for client-side scripting. In fact, HXML doesn't even support scripting, meaning all state and business logic remains in one place on the server.

Hyperview client

The Hyperview client library exposes a Hyperview React Native component that can be added to the navigation of an existing React Native app. The most important prop passed to the Hyperview component is entrypointUrl. When the component mounts, it will make a request to the entrypoint URL, expecting HXML in the response. Once the client receives the response, the HXML gets rendered on the current screen. Behaviors in the HXML will result in navigations or updates to the current screen. The client handles these behaviors by making subsequent requests for new bits of HXML, and the cycle can continue indefinitely.

In other words, think of the Hyperview client like a web browser, but for HXML. The entrypoint URL is like a hard-coded address in the toolbar, pointing at your homepage. The homepage contains links and forms that result in more requests for more HXML. The true power of the thin client becomes apparent when you realize that with a single entrypoint URL and server-driven layouts, there are endless possibilities to add and modify screens and interactions in your mobile app.

There's much more to the Hyperview client, including the ability to extend its capabilities by registering custom elements and custom behaviors. These custom elements and behaviors are like browser plugins that can provide deeper integration with your existing app or with OS capabilities like phone calls, mapping, etc.

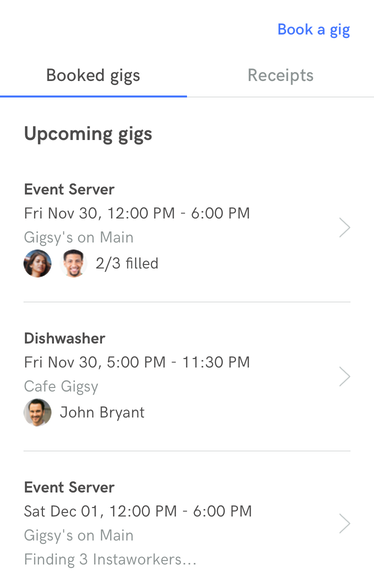

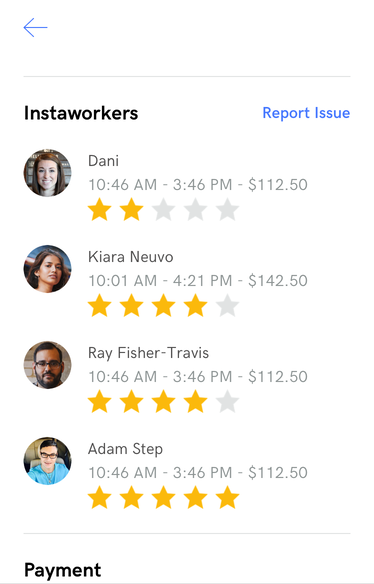

Hyperview in production

Over the last 6 months, Instawork has used Hyperview in our mobile apps to implement dozens of screens. The experience has been fantastic, and we're doubling down on our use of Hyperview in more of our core app flows. Here are just some of the advantages we've already experienced:

Focus on features, not architecture

In a thick client/JSON API architecture, developers need to make many architectural decisions when building a feature:

- How do I store the data for my feature?

- Do I extend an existing API endpoint and resource or create a new one?

- How do I model the user interactions as HTTP requests?

- Will my changes impact the performance of other clients using the same API?

- Is my API design generic enough to serve use-cases beyond the current feature I'm building?

- In order to make the design generic, am I exposing too much data?

- Are my API changes compatible with older client versions?

- What does the UI look like?

With Hyperview, the API-related architecture decisions go away, and the developer can focus on the important parts of the feature:

- How do I store the data for my feature?

- Do I extend an existing API endpoint and resource or create a new one?

- How do I model the user interactions as HTTP requests?

- Will my changes impact the performance of other clients using the same API?

- Is my API design generic enough to serve use-cases beyond the current feature I'm building?

- In order to make the design generic, am I exposing too much data?

- Are my API changes compatible with older client versions?

- What does the UI look like?

Better performance

We didn't set out to make our app faster with Hyperview, but that's exactly what happened. In our older code, screens would sometimes require data from multiple API requests before they could be rendered. With Hyperview, each screen just makes one request, significantly reducing latency. Additionally, the Hyperview response contains only the data needed by the screen, unlike generic API requests that may return extraneous data.

Instant updates

When we're ready to ship a feature, we just deploy our backend. Our apps pick up the new HXML content the next time users open the app. If we discover a bug, we just rollback our backend and 0 users remain affected. Hyperview enables Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery strategies for native mobile apps.

Consistent experience for all of our users

Since our Hyperview screens are always pulling the latest designs from our backend, we can assume that every user sees the same version and feature set. This is incredibly important for efficacy and fairness in a two-sided marketplace like Instawork. With Hyperview, we know that users aren't disadvantaged because they're using an older version of our app.

Get started today

Hyperview is truly the best way to develop networked apps for mobile devices. Based on our experience at Instawork, it takes some time to adjust to a thin-client paradigm when working with mobile apps, but once you get used to it, you will not want to go back! There are many ways to get started:

If you want to learn Hyperview by reading example code, head over to the Examples section.

To get a full sense of the elements and behaviors available in Hyperview, check out the full HXML Reference.

If you're coming from a web/HTML background, you may want to start with our guide highlighting some of the differences between HTML and HXML.

Or, to run a demo yourself, check out our Getting started guide on the next page!